Call on vendors of facial recognition to India to immediately halt the development, sale and testing of facial recognition technologies that enable mass and discriminatory surveillance.

Call on Indian law enforcement agencies to halt the procurement and use of facial recognition technologies. No amount of legal safeguards can make facial recognition compatible with human rights.

In Hyderabad, Telangana state, the government has initiated the construction of a “command and control centre” (CCC), 12 a building that connects the city’s vast CCTV infrastructure in real time. 13 Situated in Hyderabad’s Banjara Hills area, the CCC supports the processing of data from up to 600,000 cameras at once with the possibility to increase beyond this scope across Hyderabad city, Rachakonda, and Cyberabad.

Hyderabad City in Telangana state is already ranked as one of the most surveilled cities in the world. 14 15 16 17 Yet, the government has initiated the construction of a “command and control centre” (CCC), a building that connects the city’s vast CCTV infrastructure in real time. Situated in Hyderabad’s Banjara Hills area, the CCC reportedly supports the processing of data from up to 600,000 cameras at once with the possibility to increase beyond this scope across Hyderabad city, Rachakonda, and Cyberabad. 18 These cameras can be used in combination with Hyderabad police’s existing facial recognition cameras to track and identify individuals across space.

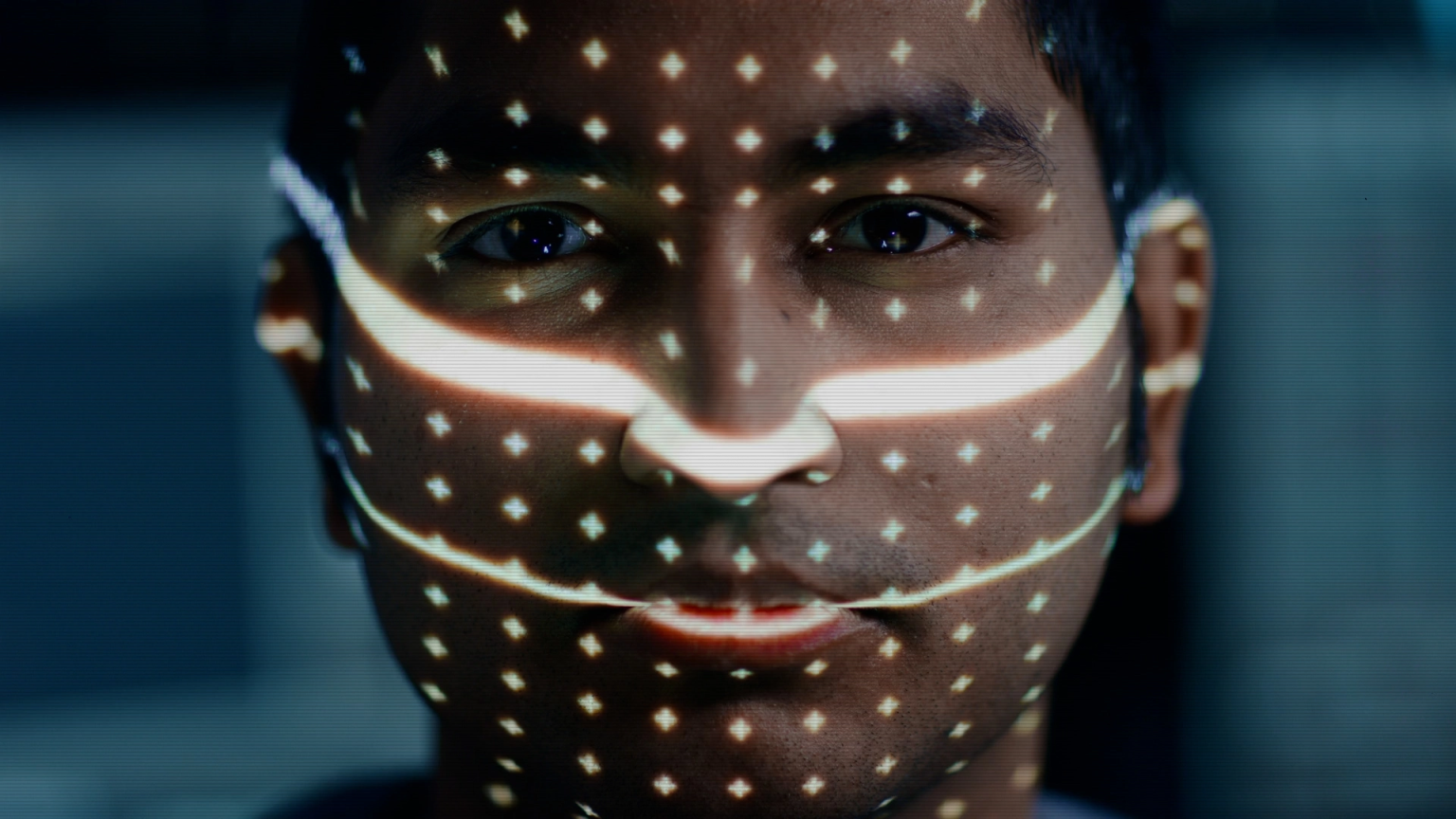

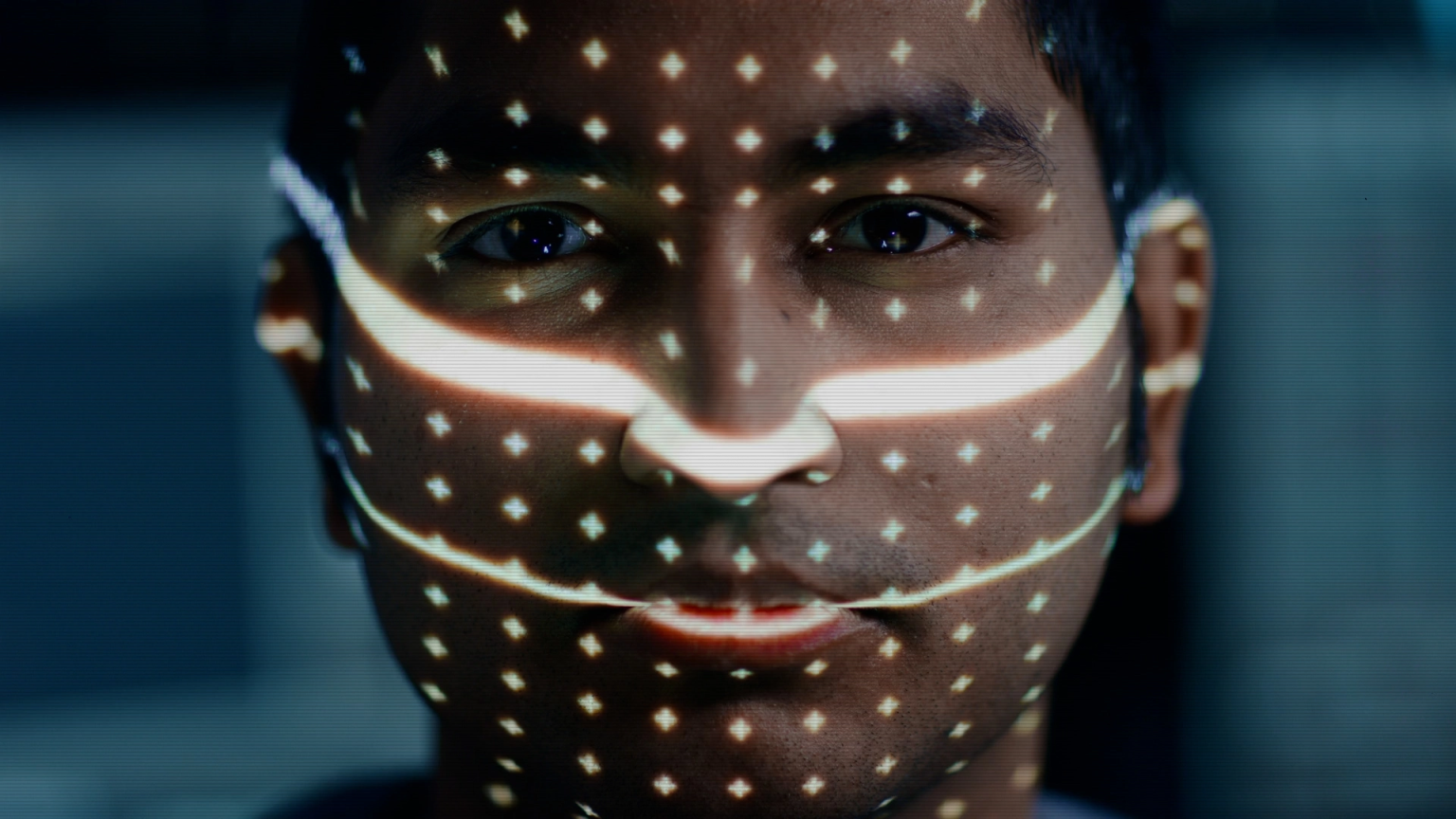

▴ The technology is developed through scraping millions of images from social media profiles, police databases, and publicly accessible sources.

Amnesty International, Internet Freedom Foundation, and Article 19’s research unearthed documents by Hyderabad Police disclosing the technical specification of their cameras, which have the capability of capturing imagery from at minimum 2 megapixels and upwards. 19 In practice, this means the cameras have a field of vision with a radius of at least 30 meters.

With the help of a group of Telangana-based volunteers, we mapped the locations of immediately visible outdoor CCTV infrastructure in two sampled neighbourhoods – Kala Pathar and Kishan Bagh, surveying areas of approximately 988,123.5 square meters and 764,207.8542 square meters, respectively. Based on this data, our analysis estimated that in these two neighbourhoods at least 530,864 and 513,683 square meters, respectively, was surveilled by CCTV cameras – that’s 53.7% and 62.7% of the total area covered by volunteers.

In addition to earlier deployments of facial recognition capable devices beyond CCTV cameras, such as tablets and other “smart” cameras, the construction of the Command and Control Centre risks supercharging the already rampant rights-eroding practice, with no regulation in place to protect civilians.

▴ CCTV surveillance as mapped in Kishan Bagh (blue) and Kala Pathar (red). Outer boundaries represent total area explored by volunteers.

Given that the Indian authorities have a record 20 of using facial recognition tools in contexts where people’s human rights are at stake, such as to enforce lockdown measures, 21 identify voters in municipal elections, 22 and – in other states in India – police protests, 23 the CCC is a worrying development. 24 There is currently no safeguarding legislation which would protect the privacy of the citizens of Hyderabad, nor a law which would regulate the use of remote biometric surveillance, which further exacerbates the danger these technologies present increase. In such a situation, the deployment and use of this technology is harmful and must be stopped.

Even without the CCC, Telangana state has in recent years been the site of increased usage of dangerous facial recognition technologies against civilians, and according to a study by the Internet Freedom Foundation, uses the highest number of facial recognition projects in India. 20

Using open source intelligence, in this case publicly available videos from twitter and news sites, Amnesty International’s Digital Verification Corps discovered dozens of purported incidents filmed from November 2019 to July 2021 showing Hyderabad police using tablets to photograph civilians in the streets, while refusing to explain why. In one case, an alleged offender was subject to unexplained biometric conscription. 26 Other cases have shown the random solicitation of both facial and fingerprint reads from civilians. 27

In May 2021, videos purportedly showed Hyderabad police asking civilians to, inexplicably, remove their masks, to obtain a biometric capture on an accompanying tablet.

▴ Hyderabad City is already ranked as one of the most surveilled cities in the world.

Under the Identification of Prisoners Act of 1920, it is not permitted to take photographs of persons by police, unless arrested or convicted of a crime – neither is the sharing of such photographs with other law enforcement agencies. As the IFF have already stated, photographic capture following mask removal of civilians by police, in this case, would be considered a violation. 28 The IFF, together with Article 19 and Amnesty International, are concerned that these tablets may be equipped with facial recognition software, against the backdrop of its increased usage by law enforcement.

When biometric surveillance is deployed for as diverse contexts as municipal elections, Covid-19 restriction compliance and unexplained stop and frisk, there’s a slippery slope towards the complete surveillance of civic life, threatening our human rights to privacy, freedom of assembly, autonomy and dignity. 29

Meanwhile, the vendors of facial recognition technologies to government agencies in India have remained woefully quiet. Amnesty reached out to the following companies to ask about their known facial recognition related activities in India, and to request they share any human rights policies they may have:

Out of the companies listed, only INNEFU responded to the letter, originally dated July 2021, stating that ‘the user agency is not under any obligation to adhere to any terms and conditions of the vendor’, without granting further responses to any of the 14 questions posed by Amnesty. Furthermore, in an earlier letter responding to questions by Amnesty for another investigation, the company made it clear that it did not have a “stated human rights policy”, but that it was in fact ‘follow[ing] the Indian laws and guidelines’.

Under international standards, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, 39 all companies have a responsibility to respect human rights, meaning they must have a human rights policy in place, and take steps to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for the risks to human rights posed by their operations and any risks they are linked to through their business relationships, products or services. Facial recognition technology inherently poses a high risk to human rights, and these five vendors have failed to demonstrate they are adequately addressing and mitigating the risks of providing this technology to government agencies

Documenting uses and abuse of facial recognition? Reach out to legal groups like IFF, or campaigning and advocacy organisations like Article 19 and Amnesty International, to seek recourse, accountability and redress

An action plan from the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (STOP)

The full extent of discrimination and mass surveillance driven by facial recognition is still largely unknown. However, it is increasingly becoming clear that facial recognition technologies are violating human rights on a global scale across multiple contexts.

Two Black men in Detroit in the United States have already filed claims of false arrest against the Detroit Police Department (DPD). In China, facial recognition is used to track and contain Uighur Muslim minorities. The Israeli Government has contracted with facial recognition firm AnyVision to assist with military surveillance throughout the West Bank, in a context where the government continues to impose “institutionalised discrimination” against Palestinians. Smart city contracts for thousands of FRT capable surveillance cameras, funded by China, are due to be installed in the Mongolian city of Ulaanbaatar. In New York City, where Atlantic Plaza Towers residents and Black Lives Matter protesters have already been targeted by facial recognition, Amnesty’s research has shown that at least 15,000 cameras can be used for facial recognition of residents.

It is quick and simple, and you can do it no matter where you are based! You can help us remind companies of their obligations to uphold our human rights, by calling on them to cease the development and sales of facial recognition to law enforcement in India. Use the suggested text in the letter generator below and feel free to add your own customisations. When you’re ready, simply hit ‘Act Now’!

The use of facial recognition technology has been identified as harmful for communities across the globe. Calls for bans have been gaining momentum with multiple jurisdictions across the Global North implementing permanent bans or temporary moratoriums on the use of the technology. However, similar calls for actions have not gained traction in the Global South, including in India.

In India, the Internet Freedom Foundation, through its Project Panoptic, has called for a ban on the use of this technology, specifically by government entities, police and other security/intelligence agencies. It has also urged the government to halt all ongoing facial recognition technology projects being developed and deployed at the Central and State level until legislation is passed that provides sufficient privacy safeguards.

In the European Union, Belgium and Luxembourg have already banned the use of this technology within their jurisdictions. However, with various other countries on the path of using this invasive technology on its citizens, civil society organisations like EDRi have spearheaded campaigns calling for a wider ban on biometric mass surveillance practices. The “Reclaim Your Face” campaign calls on the European Commission to strictly regulate the use of biometric technologies in order to avoid undue interference with fundamental rights.

Similarly, in the United States, multiple city & state level bans and moratoriums have been imposed but use of FRT is progressing fast. To combat this, on June 3, 2019, the ACLU led over 60 privacy, civil liberties, civil rights, and investor and faith groups in urging the US Congress to put in place a federal moratorium on FRT for law enforcement and immigration enforcement purposes until they fully debate what, if any, uses should be permitted. The coalition included, among others, organisations such as Fight for the Future, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Algorithmic Justice League and the Georgetown Center for Privacy and Technology. Despite the difficult fight at the federal level, we have seen bans in San Francisco (June 2019), Boston (June 2020), Portland (September 2020), and a limited ban on usage in schools in New York State (December 2020).

There is also a wider global coalition of more than 200 civil society organizations, activists, technologists, and other experts from around the world who came together in June 2021 to unite against the use of this technology. Led by Access Now, the coalition released a statement in which they called for a global ban on the use of biometric surveillance technologies that enable mass and discriminatory surveillance. This statement was drafted by Access Now, Amnesty International, Article 19, European Digital Rights (EDRi), Human Rights Watch, Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), and Instituto Brasileiro de Defesa do Consumidor (IDEC).

The Ban the Scan campaign is brought to you in partnership with New York City-based privacy, civil liberties and human rights organizations, who have called for a ban on government uses of facial recognition technologies.